Over the last 100 or so years, medical research has exploded with developments and advancement, with new treatments being established, life expectancies constantly increased, and new disease mechanisms posited, explored, and revised. Alongside treatments, new methods to conduct research are also constantly changing, taking advantage of novel technologies, allowing researchers to answer more complex questions, more quickly, than ever before[1,2].

Over the last 100 or so years, medical research has exploded with developments and advancement, with new treatments being established, life expectancies constantly increased, and new disease mechanisms posited, explored, and revised. Alongside treatments, new methods to conduct research are also constantly changing, taking advantage of novel technologies, allowing researchers to answer more complex questions, more quickly, than ever before[1,2].

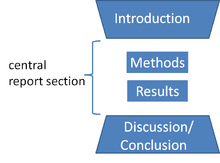

Yet, despite all this advancement, the way we write and report the findings from our research hasn’t really changed all that much in this same 100-year time frame. The ‘IMRAD’ model (Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion) of writing academic papers appeared in the mid 20th century, and still forms the backbone of how we write papers today[3].

Take, for example, this article by Raistrick et al. (1948) on streptomycine[4]. Aim, Methods, Results, Conclusion are all present. The research might now be considered out of date; the methods might appear quaint compared to current techniques, but the paper’s structure is unmistakeably similar to what we have now. The results are presented in tables, with a limited amount of narrative either side that explain why the results are there, where they’ve come from, and what this means. The exact analysis is only described at a high level. There’s a lot of data processing and analysis that has been hidden from view, and only the polished parts form the results section.

When the analysis is relatively straightforward, then this isn’t a problem – the papers will contain pretty much everything we need to understand how those results came about. But analyses nowadays are increasingly complicated, multi-stage affairs which might have several data preparation algorithms even before the analysis is considered. If some observations are missing, for example, clever multiple imputation methods might have been used to correct for potential biases. Interesting algorithms that process free-text records into bite-sized quantifiable datapoints might have been used. Do any of the inner workings of these data processing steps end up in the paper? Not often, particularly if the journal has a word limit: there simply isn’t the space.

Is that transparent?

Can we be confident we can reproduce these results with only this information?

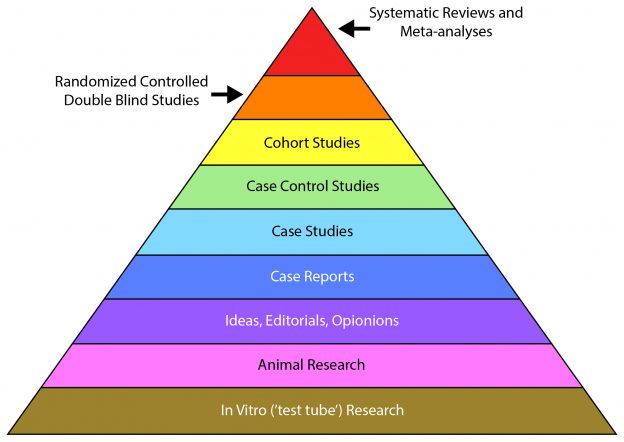

Compounding this issue is the shift in how we use these papers. There is an increasing focus on amalgamating and reusing datasets – meta-analyses, for example – or reanalysing datasets in the light of new methods. Without the datasets and the code, and enough detail on what was actually done with respect to the analysis, we’re forced to badger corresponding authors with emails, hoping for a response.

Is this efficient?

Or is there another way to write papers that gives us the detail we need for transparent, reproducible research?

At EBMLive I’ll be discussing ‘Literate Programming’, an approach which interweaves text and code, melding analysis and writing to generate manuscripts with the code embedded inside. If you’d like to hear more, it’d be great to see you there.

References

[1] World Health Organisation. From MDGs to SDGs: General Introduction. Heal. 2015 from MDGs to SDGs, 2015.

[2] British Medical Association. The Changing Face of Medicine and the Role of Doctors in the Future 2017:1–23.

[3] Sollaci LB, Pereira MG. The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: a fifty-year survey. J Med Libr Assoc 2004;92:364–7.

[4] Medical Research Council. Streptomycin Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Medical Research Council Investigation. BMJ 1948;2:769–82. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4582.769.

[5] Chalmers I. Why the 1948 MRC trial of streptomycin used treatment allocation based on random numbers. J R Soc Med 2011. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.11k023.

[6] Crofton J. The MRC randomized trial of streptomycin and its legacy: A view from the clinical front line. J R Soc Med 2006. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.10.531.

Conflict(s) of interest

None.

Biography

Matt Parkes is a 2019 Doug Altman Scholarship recipient and a research statistician at the University of Manchester, in the ROAM (Research in Osteoarthritis Manchester) unit, a group specialising in conducting late phase clinical trials of nonpharmacological interventions for osteoarthritis. His research interests include chronic disease clinical trials methods, outcome research, and digital epidemiology. He is particularly keen to explore ways of improving transparency, reproducibility, and collaboration in research.