Hamish Chalmers

As a primary school teacher turned education researcher I was delighted to have been invited to attend Evidence Live (see here) at the end of June. Education at ‘the chalkface’ has undertaken somewhat of an evidence-based turn recently. Many say that this turn is modelled on the approach to evidence in healthcare. As such I was keen to compare the content and the tone of the conversation around evidence in both these broad fields.

Ground zero for the evidence-based turn in education is probably the 2013 briefing paper, written by the CEBM’s very own Ben Goldacre for then Secretary of State for Education, Michael Gove. Its principal message was to urge more randomized trials to assess the effects of educational interventions. Largely in response to this, Tom Bennet, a teacher and columnist for the Times Educational Supplement, founded researchED, a grassroots forum for teachers and educationalists to talk about the role of evidence at the education chalkface. These events coincided with the designation of the Educational Endowment Foundation (EEF) as the government’s What Works centre for improving educational outcomes for school-aged children. In the five years of its existence, the EEF has overseen more government funded randomized trials into the effects of educational interventions than the entirety of human history that preceded it (prior to the EEF, the DfE had apparently funded just two randomized trials. At time of writing the EEF has funded 106).

While this evidence-based turn has excited conversations among teachers about the intersection between research and practice, it has not been universally welcomed. The response from many established educationalists has been one of vitriol. Gary Thomas has described the term ‘what works’ in education as a “sublinguistic grunt”. Frank Ferudi urged us to “keep the scourge of scientism out of schools”. A standard methodology text for postgraduate educational researchers describes randomized trials of educational interventions as “belonging to a discredited view of science as positivism”. And Dylan Wiliam claims that “teaching will never be a research based profession” and “that is a good thing”.

A recurring theme in these rejections of evidence-based education (EBE) is an apparent obsession with juxtaposing medical epistemology unfavourably against educational epistemology. Rather than seeing the developmental trajectory of evidence based medicine (EBM) as something by which we might learn about our own journey into enlightenment, some educationalists claim that the former is so fundamentally different to the latter that any attempts to extrapolate lessons from it are fruitless. Justifications for this position are articulated something like this: complex interventions cannot be understood using RCTs; children are not molecules in test tubes; in education you can’t control for all possible confounders; the aim of medicine is to make people well, and such a neatly defined purpose for education does not exist. From where I sit this looks very like the charges of “cookbook medicine” laid against early champions of EBM. Evidence Live was an ideal opportunity to consider how this mischaracterization had been and is being dealt with in healthcare, with a view to understanding how it might be approached in education.

As John Ioannidis reminded us in his keynote at EvidenceLive, twenty years ago David Sackett and colleagues defined EBM as “integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence.” It might come as a surprise to some education commentators that EBM is so concerned with the role of the practitioners. The aforementioned Gary Thomas, responding to Goldacre’s 2013 paper, stated that “we shouldn’t replace trust in […] teachers’ experience with a faith in trials.” One wonders how he arrived at the idea that Goldacre (or anyone else for that matter) ever advocated replacing teacher expertise with fair tests of teaching approaches. Notwithstanding that Thomas takes the opposing view – that teacher experience is all and the value of trials is negligible – he articulates an important point: EBE is incomplete if it only relies on evidence from intervention studies.

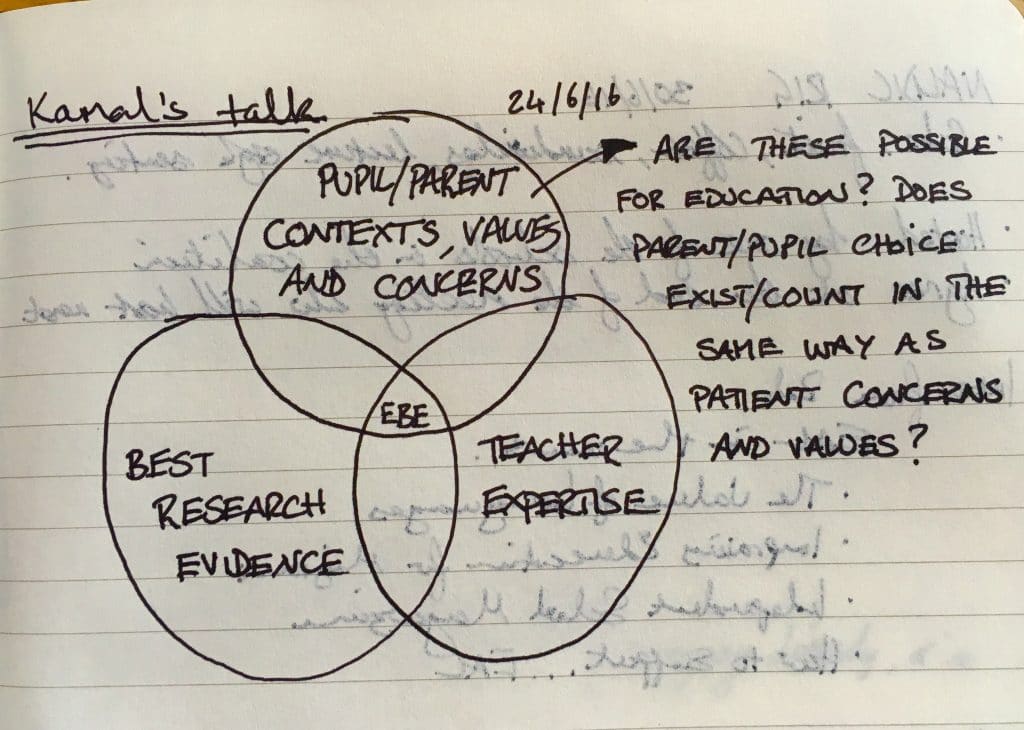

EBE must consider, as EBM does, research evidence together with practitioner expertise. In EBM, however, clinical expertise and best external evidence do not constitute the whole picture. Kamal Mahtani demonstrated this in his talk by sharing another two-decades-old iteration of a definition of EBM that places it at the intersection of best research evidence, clinical expertise and patient concerns and values. What is the implication of this expanded view of EBM for a burgeoning movement towards EBE? Eavesdropping on philosophical discussions about education will make clear that education’s purpose is far from universally agreed. Teachers, parents and pupils all have their own ideas about what they want from it. Acknowledging the interplay between these three components in a model for EBE might help to engage constructively those who believe the EBE movement is trying to ‘manualize’ education. However, while external evidence and practitioner expertise have clear corollaries in education, the capacity for end users to inform EBE is less clear than the capacity of patients to shape EBM.

In consultations with patients, doctors can use their knowledge of research evidence and their clinical experience in conjunction with what the patient wants (pain relief, fatigue management, a new hip, a longer life, or a humanely managed death). Patients can define what healthcare means to them and urge their healthcare providers to take account of that. Education is constrained by factors that will not accommodate personal choice in the same way. The overarching purpose of state education is mandated by the architects of the National Curriculum, not directly by the concerns and values of individual pupils, parents and teachers. Education, by and large, is delivered en masse, meaning that any individual concerns and values that might reasonably be assumed to be acted on must be homogenized. Moreover, the specific methods by which individual schools and teachers deliver this mass intervention are micromanaged by regulatory bodies such as OFSTED. This not only compromises pupil/parent choice but constrains teachers in their use of both personal expertise and external evidence.

While the model of EBM that Mahtani shared describes an ideal that might help to provoke productive rather than adversarial discussions about EBE, can EBE be defined in those terms? One might argue that a certain level of decoupling from state-prescribed education might now be possible as schools convert to Academies, and Free Schools are established to address aspirations of various interest groups. Nonetheless, the iron fist of curriculum oversight and pedagogic control is still centrally imposed. To give an example of this tension, Europa School UK in Culham, Oxfordshire, where I am a governor, is a Free School established with the explicit aim of providing bilingual education to the children of parents who have made clear that this matters to them. Despite fairly strong evidence of the positive effects of teaching all subjects in two languages, the DfE has insisted that beyond age 11 maths must be taught only in English. In this one act they shatter all three of the circles in Mahtani’s Venn diagram.

My challenge then, to myself and to my colleagues within and outwith education struggling to arrive at an acceptable and realistic conceptualization of what EBE really means, is to consider the sketched provocation that I tweeted from my seat at Evidence Live (below). Is the EBM definition applicable to EBE? If not, how can/should it be adapted so that it is? Or is Dylan Wiliam right to insist that even on its own terms education can never be research-based?

You can follow Hamish at https://about.me/hchalmers